Charge of the Light Brigade Anniversary Tours

Friday 25th October 2024 marked the 170th anniversary of the Charge of the Light Brigade, a charge of British light cavalry led by Major-General James Thomas Brudenell, 7th Earl of Cardigan, against the Russian Military Forces during the Crimean War. To mark this year’s anniversary, we hosted a series of special tours focussing on the early life of the 7th Earl, the infamous charge, war-time media, and the Balaklava centenary dinner held at Deene on Saturday 20th November 1954.

James Thomas Brudenell

James Thomas Brudenell

James Brudenell was born on 16th October 1797 at a manor house in Hambleton, Buckinghamshire, to Robert Brudenell and Penelope Cooke. Robert and Penelope had 8 children, and with James being the only son it is said that he was over-indulged and developed into a spoilt child accustomed to getting his way.

Educated at Harrow, James showed intellect in various subjects including Greek and Latin. He was a good rider who was inspired by the Cavalry at Waterloo, so he sought to purchase a commission in a regiment, but his Father would not allow it fearing it would risk the family line of succession. In 1815 James was sent to Christ Church Oxford, where he was automatically granted admission with no examination because he was an aristocrat. Still, he left in his 3rd year without taking his degree.

At the age of 22, James formed his own troop of horse to guard against possible reformist demonstrations in Northamptonshire. James’ climb up the military ladder officially began at the age of 27, when he joined the 8th Kings Royal Irish Hussars.

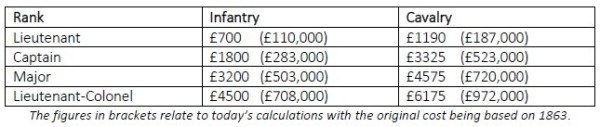

James took advantage of the commission’s system and purchased his Lieutenancy in January 1825, became a Captain in 1826, a Major in August 1830, and finally a Lieutenant-Colonel in December 1830. James obtained command of the 15th Kings Hussars, one of the finest cavalry regiments, at the reported cost of £35,000.

The practice of purchasing a commission began in 1683 during the reign of His late Majesty King Charles 2nd and was abolished on November 1st 1871. The purchase price of a commission was a cash bond for good behaviour, liable to be forfeited if the Officer in question was found guilty of cowardice, desertion or gross misconduct.

James wanted the King’s Hussars to be the smartest, most efficient regiment, but his strict rules and harsh drills resulted in overworked horses, tired men, and an ever-increasing troop debt. His youth, inexperience, and arrogance led to him being censured in 1834 for reprehensible conduct, resulting in a dismissal by King William. After a period of enforced retirement, James was back in favour, and he took command of the 11th Light Dragoons (later Hussars).

Lord Cardigan and The Charge of the Light Brigade

James gained permission from Lord Harding to travel independently of his Brigade to the seat of war. Lord Cardigan left London for Paris on May 8th aboard his yacht, the RYS Dryad. He gave a dinner party at the Café de Paris on the 10th and was entertained by Napoleon III and Empress Eugenie, leaving Marseilles by French steamer on the 16th. On May 24th the ship anchored off Scutari, the British base where he met Lord Lucan, his immediate commander and Brother-in-Law.

On October 25th 1854 the Russians were threatening to take Balaclava and were assembled in great numbers at the end of a valley behind a battery of heavy guns with further guns on the flanks overlooking the valley. Through a misunderstanding over an order from Lord Raglan to Lord Lucan, the latter ordered Lord Cardigan to advance on the enemy down the valley. Lord Cardigan saluted Lord Lucan and on taking his place some 5 horse lengths in front of his Brigade was heard to mutter “Here goes the last of the Brudenells”.

The Brigade was in three lines and Cardigan led them at a brisk trot down the valley. Men and officers soon began to fall under the heavy fire, but in a few minutes they had reached the guns and sabred most of the Russian gunners, and on passing through were confronted by 5,000 Russian cavalry and a mass of infantry. Eventually, the officers rallied the remnants of the Brigade and returned up the valley. 113 of all ranks were killed, 134 wounded and 475 horses killed. 195 mounted men remained out of the original 675.

|

|

|

|

In a letter to his Brother-in-Law, Lord Howe, three days after the battle, Lord Cardigan wrote,

“I’ve been in a serious affair, and my brigade is almost destroyed. My opinion is that Lt General (Lord Lucan) ought to have had the moral courage to disobey the order…I led the attack…the shower of grapeshot and round shot for ¾ of a mile was awful…almost every officer, but myself was either killed, or wounded, and how I escaped, being in front, and more exposed than anyone is a fearful miracle and I am most grateful to the Almighty for such an intervention of Divine Providence. I considered it certain death but led straight and no man flinched…”

Arrogant he may have been, but no one can dispute his courage or that of his officers and men. Lord Cardigan received a hero’s welcome on his return and was required to give his account of the action to the Royal family – an event recorded in James Sant’s painting in the White Hall at Deene Park. Queen Victoria is supposed to have been included in the painting originally, but to have insisted on being removed when she discovered more about Cardigan’s private life.

The First Media War

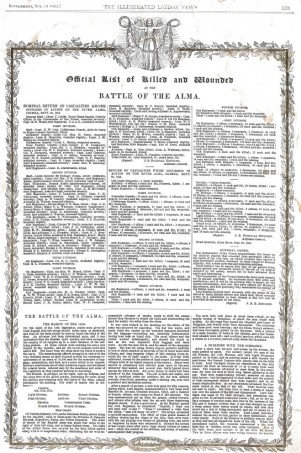

Crimea was the first war in a new age of mass communications, with newspapers sending their war correspondents overseas to report from the front line and telegrams helping news travel faster.

Crimea was the first war in a new age of mass communications, with newspapers sending their war correspondents overseas to report from the front line and telegrams helping news travel faster.

With permission from Lord Harding, the Times newspaper sent their war correspondent, William Howard Russell, to Crimea and he accompanied the Guards Brigade. This was a significant move in journalism: for the first time, the actualities and horrors of war were brought to the breakfast tables of Britain. William Howard Russell won lasting fame for revealing the poor medical facilities for wounded troops and his report about the Charge of the Light Brigade during the battle of Balaclava.

Russell spent 22 months covering the Crimean War including the siege of Sevastopol and the Charge of the Light Brigade.

In March 1855 Roger Fenton arrived in Crimea, under the instruction of a commercial gallery to record the war. Roger was very conscious of his relationship with the Royal Family, and he operated under considerable self-censorship, which is why his photographs do not contain any images of dead bodies.

He stayed until June 1855 when cholera forced him to return to England with 360 photographs taken under very difficult conditions. On his return, he was summoned to Buckingham Palace by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert to gain first-hand reports of his travels.

When Roger’s photographs were exhibited in London in 1855 a report stated that ‘the stern reality stands revealed to the spectator. Camp life with all its hardships mixed occasionally with some rough and ready enjoyments, is realised as if one stood face to face with it’.

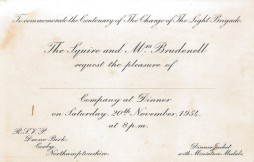

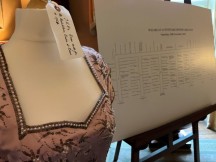

The Balaklava Centenary Dinner

In early 1954 George Brudenell, his wife Mary, and their son Edmund, began the preparations for a grand Centenary Dinner to remember the brave soldiers who fought at Balaklava. With an impressive guest list, including the Duke of Edinburgh, the Duke of Gloucester, and representatives of the soldiers who fought at Balaklava, it was a huge undertaking and required months of planning. We are fortunate that documents, letter correspondence, draft table plans, and catering quotations were all kept and now form part of our archive.

Correspondents from The Times and The Daily Telegraph were invited to attend, and a BBC Radio broadcast by Godfrey Talbot gave listeners an insight into the evening itinerary, guest list, guest attire, and the history of the Charge.

The event was a success and enjoyed by all who attended. In the months that followed, the family received many thank-you letters, all of which are safely stored in our archive.

One such letter was received from Major General Hon. Gerald Scarlett, who attended on behalf of his Great Uncle.

‘Dear Mrs Brudenell,

I am so grateful to you and the Squire for your very great kindness in asking me and my wife to attend your magnificent Centenary Dinner at Deene Park, and we send you our very warm thanks.

I and my family are highly honoured to think that I was allowed to represent my Great-Uncle and to be able to join in the tribute paid to the memory of the gallant Light Brigade. From my early childhood I was brought up on the tradition of the actions at Balaklava which have always been a great inspiration to me as one of the greatest examples of devotions to duty.

May I again express my thanks and say how honoured I am to have been the guest of the Squire and yourself on the great occasion.

Yours sincerely,

Gerald Scarlett.’

|

|

|

|