Garden Blog - Nov '24

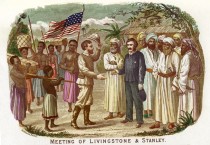

On the 10th November 1871, near Lake Tanganyika, explorer and journalist, Henry Stanley, uttered the now famous line, ‘’Dr. Livingstone I presume?’’.

Dr. Livingstone, a staunch Christian, had travelled to Cape Town in March 1841, as a missionary intent on converting the locals. Besides spreading the word of God, Livingstone had another goal in mind – to discover the source of the White Nile, and he devoted many expeditions across Africa to this end. Sadly, for Livingstone, he was unable to achieve either goal. He only managed to convert one African, a tribal leader by the name of Sechele. However, Sechele found the Christian rule of monogamy rather arduous, and soon lapsed. Although Livingstone never did find the source of the Nile, he did find the source of the Congo, which in itself is no mean feat, and a pretty good consolation prize.

After a while, folks started to think that poor Livingstone was dead. His letters had not been reaching home, he had lost or been robbed of all of his possessions, and was known to have been terribly ill. There were, however, people who travelled into Africa intent on tracking Livingstone down, one such person, sent by the New York Times, was Henry Stanley.

Having been discovered alive, Livingstone lived for another eighteen months, dying on 4th May 1873. His heart was buried where he died, at Ulala, and his body and papers were carried on an epic journey to the coast and on to Britain, where he was interred in Westminster Abbey.

By now, you are most likely asking yourself, ‘what does any of this have to do with gardening?’

Well, hacking your way through the jungles of Africa, either exploring or looking for Livingstone, is reminiscent of us gardeners hacking our way through the borders, clearing them of herbaceous plants that have died back as autumn tightens its grip.

Herbaceous plants that have passed their glory days of summer and are now rapidly deteriorating and dying down need cutting back and clearing away. By carrying out the task now, not only do our borders look tidy, but it also allows light to plants such as primroses to stimulate flowering in spring and ensures that we are not trampling emerging spring bulbs by leaving the job too late. The plant material removed can be added to the compost heap, and when well-rotted, returned as a top dressing. It is important, however, to ensure that any weeds with seed heads, or pernicious weeds such as bindweed or ground elder are kept aside and destroyed.

On the subject of keeping our gardens tidy, it’s important to remove regularly the fallen leaves from lawns, as they will otherwise suffocate and kill the grass beneath, leading to a patchy lawn. Leaves left to lie on the ground also harbour pests and diseases that will cause unnecessary damage. Gathered leaves can quite simply be piled up in the same manner as a compost heap, covered with old carpet or tarpaulin and allowed to break down naturally. This time next year you will have lovely crumbly leaf mould to add to your borders.

Having diligently laboured in our gardens, ensuring that they are properly tended, it’s worth taking a little time, cuppa in hand, to amble about and enjoy the kaleidoscope of colour produced by so many deciduous trees and shrubs as they shed their leaves.

But why do they change colour? Here’s the science bit! Leaf colour comes from the pigments they contain. These substances are produced by leaf cells to help them obtain food. The three pigments that colour leaves are chlorophyll (green), carotenes (yellow) and anthocyanins (reds and pinks). Chlorophyll production, which gives leaves their green colour, comes to a gradual halt during autumn, and existing chlorophyll within leaves is destroyed by cold weather, resulting in carotenes and anthocyanins becoming visible and producing the autumn colours that we all love so much. The strength and balance of those colours is controlled by a multitude of environmental and weather factors that are rather on the complex side, so let’s not get too bogged down in detail, just stand back and admire the show.

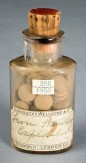

At this point, let’s ponder a little more on the achievements of Dr. Livingstone. He contracted malaria an astonishing thirty times, and patented a medicine called ‘Livingstone’s Rousers’ with which to control it. A mixture of quinine, rhubarb and a purgative called jalap, ‘Livingstone’s Rousers’ was to be knocked back with sherry. This sounds like it would rouse any drowsy gardener, however jaded at the end of a working day.